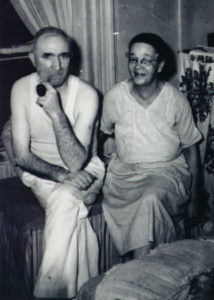

My great-grandmother, Myrtle Mae (Robinson) Yee Mitchell (right), was vague about her racial heritage. She was African American, but for many years passed herself off as something else.

MECHANICSVILLE, Va. – Today, with clashes between white supremacists and neo-Nazis and those who oppose them in nearby Charlottesville, Virginia, today, I had something happen to me that feels like a total betrayal.

Today, an African-American man told me – despite my pointing out my ancestry and life experience – that I had no business commenting on the experiences of African slaves and their descendants because I was “white,” and that I should “own it.”

Sure, if you judge me by my skin color – as a racist would – I look white. I had likewise once been told by a white former friend with whom I’ve since split (largely because of that former friend’s racist attitudes) that I was white and that I should “own it.”

I should “own” being white!

I’d love to know how I should “own” being white?

The fact is that I’ve never felt fully welcome – or comfortable – in white society. I grew up with the one-drop rule. All my life I have listened to whites tell me how wrong it is for the races to mix, especially in the genes of a single individual. To be fair, I have encountered similar attitudes among those of non-white descent.

Tribalism runs deep.

Some of my ancestry was a mystery to me, whether by design or accident, I don’t know. I grew up knowing I was part Chinese. This was enough to get my mom and I threatened with death by the Ku Klux Klan when my dad – newly discharged from the U.S. Air Force – moved us back to his home state of Louisiana afterward.

I was somewhat sheltered by the fact that I grew up next door to my great-great aunt, Lucy Stout, who despite growing up with the typical Southern antipathy toward other races, loved my mom and I as the family members we were.

But not all our neighbors were so tolerant. When an obviously black family tried to move into the neighborhood, someone shot up their house. The family moved out the next day. It doesn’t take much imagination to figure out how they would have treated us if they had known about my mom’s and my African ancestry.

Back then, being Asian was bad enough. We moved to Louisiana just before the big buildup of American troops in Vietnam, and many of my friends and neighbors weren’t too picky about what group of Asians they were going to hate.

The hostile atmosphere in the Vietnam era was similar to what my mom and grandmother experienced in World War II. The Chinese were allies, but too many “red-blooded” Americans assumed any Asian – East Asian, at least – was Japanese, thus the enemy, until proven otherwise.

—

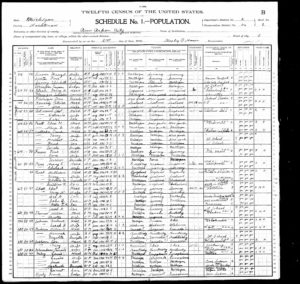

My great-grandmother, Myrtle Mae Robinson (aka Robison) is on line 91 of this page from the 1900 U.S. Census of Ann Arbor, Michigan. The race given for her and her parents, William A. and Harriett Robison (sic) is black.

My black ancestry was something of a surprise. My grandmother, Yut-Seul Yee, may not have known her mother’s family – my great-grandmother, Myrtle Mae Robinson, did not seem to get along well with her father (William Robinson), and her mother (Hannah Marie Woods) had died while she was young.

Somehow, the story got passed down that my great grandmother was half Chinese and half Spanish (though not Mexican!) and that she was born in Santa Barbara, California. That is what my mom believed when she joined the U.S. Air Force – that’s what she recorded in her official biographical statement.

Many years later, when I was in Ohio on business, I did some digging in Dayton records and learned that my great grandmother was listed as either colored or negro in the birth and/or death records of her children – my grandmother had two siblings, both of whom died very young.

Later, I started finding more and more documents that showed she grew up with a black family in Ann Arbor, Michigan. I also did some genetic testing and found out that yes, I had African ancestry. I eventually realized that the records were right. The story my mother was told was fiction. My great-grandmother was African American. She was born in the Midwest – where exactly is not yet clear – not in California.

The African side of my family were apparently slaves. Their history is murky.

Hannah Woods background is more straightforward. She is listed as black in U.S. Census records. She was born in 1861 in Kentucky. I suspect she was a slave, or maybe the daughter of freed slaves, but the identity of her parents – also born in Kentucky – is not entirely clear given the available records.

William Robinson’s history is a bit more challenging. He was born in Canada to parents of African descent. Both parents had ties to slaveholding states. His father, John Alexander Robinson, was born in Kentucky. His mother, Harriett Ann Taylor, was born in Canada, but her parents were both born in Maryland. My guess is one or both families took a railroad north before the Civil War, then moved back to the United States after emancipation.

My great-grandmother tried to pass for something other than black. It seems a family tradition. Her paternal aunts and uncles had a range of skin tones. Those who could pass for white, did so. Those like her father who were too dark to do so, could not deny the obvious. Despite Myrtle Robinson’s efforts, it appears she couldn’t either.

—

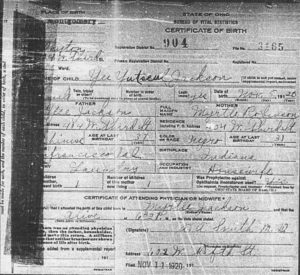

This is the birth certificate for my grandmother, Yut Seul Yee. The race of her father, Yee Jackson, is listed as Chinese and that of her mother, Myrtle Robinson, is listed as Negro.

Given that I passed for white and grew up in a white neighborhood, I never experienced the most obvious expressions of racism – certainly not the educational and job discrimination I would not have escaped had my skin been darker or my epicanthic folds more pronounced.

But I wonder if what I experienced was worse? It was certainly different. Whites, thinking I was one of them, were rather unfiltered in expressing around me their opinions of other races and ethnicities. I was the mole – the spy, gathering intelligence (willingly or otherwise) on how much my kindred were despised by white society.

I saw how the code words changed, from open expressions of hatred – such how the use of words like “nigger” morphed into more politically acceptable code like “welfare queen.” Same old racism, just a more public relations-friendly expression.

In the interest of surviving, I usually managed to suppress my anger at the hatred I experienced. As I get older, it gets harder to accept – and to keep quiet about it. I shouldn’t have had to put up with the racism I encountered then. I shouldn’t have to put up with it now.

Over the years, I’ve experienced racist treatment from whites, but also Chinese (because I’m not Chinese enough) and also African Americans – because I either pass or fail (depending on one’s perspective) the paper bag test. Why am I not good enough for those who share some of my ancestral history of oppression? Sure, some of my ancestors were the oppressors, but that doesn’t make my other ancestors any the less oppressed. And it does not negate the racism I encountered in my youth and beyond.

—

Rodney King, in the aftermath of the riots that followed the inexcusable acquittal of the four white police officers who severely beat him during a Los Angeles traffic stop, asked, “Can’t we all get along?”

Personally, I would love to. But I’m not going to do it by acting as if large groups of my ancestors never existed. They did. I carry some of their blood and some of their experience forward to share with new generations.

If some don’t like it, tough. I’m not going to disappear just so they can feel more comfortable in their bubble.

–30–

What race(s) should I own?

Posted by AbyssWriter on 8/13/17 • Categorized as Commentary,Race

My great-grandmother, Myrtle Mae (Robinson) Yee Mitchell (right), was vague about her racial heritage. She was African American, but for many years passed herself off as something else.

MECHANICSVILLE, Va. – Today, with clashes between white supremacists and neo-Nazis and those who oppose them in nearby Charlottesville, Virginia, today, I had something happen to me that feels like a total betrayal.

Today, an African-American man told me – despite my pointing out my ancestry and life experience – that I had no business commenting on the experiences of African slaves and their descendants because I was “white,” and that I should “own it.”

Sure, if you judge me by my skin color – as a racist would – I look white. I had likewise once been told by a white former friend with whom I’ve since split (largely because of that former friend’s racist attitudes) that I was white and that I should “own it.”

I should “own” being white!

I’d love to know how I should “own” being white?

The fact is that I’ve never felt fully welcome – or comfortable – in white society. I grew up with the one-drop rule. All my life I have listened to whites tell me how wrong it is for the races to mix, especially in the genes of a single individual. To be fair, I have encountered similar attitudes among those of non-white descent.

Tribalism runs deep.

Some of my ancestry was a mystery to me, whether by design or accident, I don’t know. I grew up knowing I was part Chinese. This was enough to get my mom and I threatened with death by the Ku Klux Klan when my dad – newly discharged from the U.S. Air Force – moved us back to his home state of Louisiana afterward.

I was somewhat sheltered by the fact that I grew up next door to my great-great aunt, Lucy Stout, who despite growing up with the typical Southern antipathy toward other races, loved my mom and I as the family members we were.

But not all our neighbors were so tolerant. When an obviously black family tried to move into the neighborhood, someone shot up their house. The family moved out the next day. It doesn’t take much imagination to figure out how they would have treated us if they had known about my mom’s and my African ancestry.

Back then, being Asian was bad enough. We moved to Louisiana just before the big buildup of American troops in Vietnam, and many of my friends and neighbors weren’t too picky about what group of Asians they were going to hate.

The hostile atmosphere in the Vietnam era was similar to what my mom and grandmother experienced in World War II. The Chinese were allies, but too many “red-blooded” Americans assumed any Asian – East Asian, at least – was Japanese, thus the enemy, until proven otherwise.

—

My great-grandmother, Myrtle Mae Robinson (aka Robison) is on line 91 of this page from the 1900 U.S. Census of Ann Arbor, Michigan. The race given for her and her parents, William A. and Harriett Robison (sic) is black.

My black ancestry was something of a surprise. My grandmother, Yut-Seul Yee, may not have known her mother’s family – my great-grandmother, Myrtle Mae Robinson, did not seem to get along well with her father (William Robinson), and her mother (Hannah Marie Woods) had died while she was young.

Somehow, the story got passed down that my great grandmother was half Chinese and half Spanish (though not Mexican!) and that she was born in Santa Barbara, California. That is what my mom believed when she joined the U.S. Air Force – that’s what she recorded in her official biographical statement.

Many years later, when I was in Ohio on business, I did some digging in Dayton records and learned that my great grandmother was listed as either colored or negro in the birth and/or death records of her children – my grandmother had two siblings, both of whom died very young.

Later, I started finding more and more documents that showed she grew up with a black family in Ann Arbor, Michigan. I also did some genetic testing and found out that yes, I had African ancestry. I eventually realized that the records were right. The story my mother was told was fiction. My great-grandmother was African American. She was born in the Midwest – where exactly is not yet clear – not in California.

The African side of my family were apparently slaves. Their history is murky.

Hannah Woods background is more straightforward. She is listed as black in U.S. Census records. She was born in 1861 in Kentucky. I suspect she was a slave, or maybe the daughter of freed slaves, but the identity of her parents – also born in Kentucky – is not entirely clear given the available records.

William Robinson’s history is a bit more challenging. He was born in Canada to parents of African descent. Both parents had ties to slaveholding states. His father, John Alexander Robinson, was born in Kentucky. His mother, Harriett Ann Taylor, was born in Canada, but her parents were both born in Maryland. My guess is one or both families took a railroad north before the Civil War, then moved back to the United States after emancipation.

My great-grandmother tried to pass for something other than black. It seems a family tradition. Her paternal aunts and uncles had a range of skin tones. Those who could pass for white, did so. Those like her father who were too dark to do so, could not deny the obvious. Despite Myrtle Robinson’s efforts, it appears she couldn’t either.

—

This is the birth certificate for my grandmother, Yut Seul Yee. The race of her father, Yee Jackson, is listed as Chinese and that of her mother, Myrtle Robinson, is listed as Negro.

Given that I passed for white and grew up in a white neighborhood, I never experienced the most obvious expressions of racism – certainly not the educational and job discrimination I would not have escaped had my skin been darker or my epicanthic folds more pronounced.

But I wonder if what I experienced was worse? It was certainly different. Whites, thinking I was one of them, were rather unfiltered in expressing around me their opinions of other races and ethnicities. I was the mole – the spy, gathering intelligence (willingly or otherwise) on how much my kindred were despised by white society.

I saw how the code words changed, from open expressions of hatred – such how the use of words like “nigger” morphed into more politically acceptable code like “welfare queen.” Same old racism, just a more public relations-friendly expression.

In the interest of surviving, I usually managed to suppress my anger at the hatred I experienced. As I get older, it gets harder to accept – and to keep quiet about it. I shouldn’t have had to put up with the racism I encountered then. I shouldn’t have to put up with it now.

Over the years, I’ve experienced racist treatment from whites, but also Chinese (because I’m not Chinese enough) and also African Americans – because I either pass or fail (depending on one’s perspective) the paper bag test. Why am I not good enough for those who share some of my ancestral history of oppression? Sure, some of my ancestors were the oppressors, but that doesn’t make my other ancestors any the less oppressed. And it does not negate the racism I encountered in my youth and beyond.

—

Rodney King, in the aftermath of the riots that followed the inexcusable acquittal of the four white police officers who severely beat him during a Los Angeles traffic stop, asked, “Can’t we all get along?”

Personally, I would love to. But I’m not going to do it by acting as if large groups of my ancestors never existed. They did. I carry some of their blood and some of their experience forward to share with new generations.

If some don’t like it, tough. I’m not going to disappear just so they can feel more comfortable in their bubble.

–30–

Share this: