[EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the text of a speech I gave at the 30th Friends of the Library Book & Author Dinner at the Indian Creek Yacht and Country Club in Kilmarnock, Va., on October 29, 2012.]

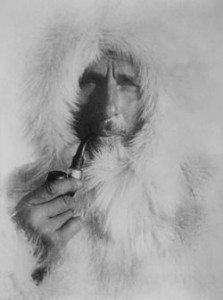

Alfred Wegener in Greenland

The theory of continental drift is 100 years old this month.

Alfred Wegener, the father of continental drift and one of the main characters of my first book, Upheaval from the Abyss, was a consummate explorer—both in the physical and intellectual realms. By October 1912, when Wegener described his theory of how the major features of the Earth’s surface rearrange themselves over geologic time, he had established himself as a pioneer explorer of the atmosphere as well as the poles. He used kites to measure characteristics of the atmosphere. He and his brother, Kurt, set an endurance record for flight in a balloon. He had been on one expedition to Greenland, and was set to go on the second of ultimately four expeditions to the ice-bound island.

His restlessness extended into his scholarly research. The main incident that triggered the events I chronicle in my book occurred in 1910, when he looked at a map and realized the similarity in shapes of the Atlantic coasts of South America and Africa were likely more than coincidence—that they had once been joined and drifted apart. In 1911, he published a major book on the thermodynamics of the atmosphere. In 1921 he published a monograph on the origin of moon craters in which he argued, on the basis of experiments he conducted, that they were created by asteroid impacts. In 1924, he and his father-in-law, Wladimir Koeppen, published a major book on earth’s past climates. And from 1915 to 1930, he published four editions of the work for which he is best know, The Origin of Continents and Oceans, in which he describes his theory of continental drift.

Throughout his too-short life—he died at age 50 on his last expedition to Greenland—Wegener, a German, embodied the frontier mythos that Americans today take for granted. He was constantly pushing the envelope, not letting geographic or academic boundaries bar him from following evidence wherever it led. He persisted in pursuing his ideas despite the withering fire of critics more interested in protecting their position than in open and honest inquiry. He did what he thought was right, even if it meant risking, and losing, his life on a Greenland glacier as he tried to ensure the welfare of men he, as expedition leader, was responsible for.

Many of the other characters in Upheaval from the Abyss embodied that as well. From Doc Ewing, who left a hardscrabble life on the Staked Plains of Texas for a life-long journey of discovery of the way the Earth, moon, and other planets worked; from the cores of young scientists and technicians—such as Al Vine, Joe Worzel, and Bruce Heezen—who joined Ewing on his quest; from Marie Tharp, who broke free of the limited suite of roles men of the time allowed women to fill, mapping the ocean floor and making the key observation that forced a scientific world that had resisted Wegener’s ideas to reconsider; none of them were content with a gray-flannel straitjacketed existence. They spent, and in some cases, gave their lives seeking to discover and understand what lay beyond the literal and figurative horizon.

Fifty years ago last month, President John F. Kennedy harnessed that frontier mythos when he launched the nation on another quest: to put send men to the moon and bring them back safely to Earth. His challenge included these famous words:

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

We lived up to Kennedy’s challenge. Most of us remember that fateful night in July 1969 when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to set foot on a world other than Earth. (I watched it with my parents on a television in a room at Perry’s Motel in Hot Springs, Ark.) That same decade we sent two men, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh, to the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench—the deepest point of the world’s oceans. In the decade or two afterward Kennedy’s speech, we sent spacecraft on a voyage beyond the boundaries of our solar system. We sent probes to Mars, Jupiter, Venus, and other planets; built a permanent outpost in space, discovered at the bottom of the ocean unique ecosystems that do not require energy from the light of the sun; decoded the genome; and nearly eradicated a number of devastating infectious diseases around the world.

But in the twenty first century the frontier mythos that drove us further seems to have fizzled. Those of us inspired by Kennedy’s words in our youth seem to have forgotten them as we age. We and our following generations have become so distracted by 24-hour non-news, unreality television, and inane online chatter that we can [scarcely] be bothered to make the sacrifices required to make the world better for us and our fellows. Where we once did what needed to be done despite cost, effort, and lives, we now fight over every last cent we can keep for ourselves and demand to know why we should do anything for anyone else.

The science that fueled the tremendous progress of the years after World War II, that made the advances I mentioned possible, and that helped change this nation from a largely agrarian backwater (with promise) into a global power, we have largely turned our backs on. It is no longer considered desirable to ask the big questions that made it possible for us to reach the surface of the moon or the bottom of the ocean. It is no longer considered worthwhile to consider the advice of scientists who spend their lives studying Earth’s life, climate, and oceans and warn us about the damage we are inflicting upon our planet—we have been told that scientists are all frauds, and we accept such assertions on faith.

Rather than embrace exploration and discovery as we had in the past, we have enthusiastically embraced what the writer and scientist Isaac Asimov once called the “cult of ignorance”:

There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that “my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.”

Nevertheless—as the rhetoric of this election season as most other election seasons remind us—we love to tell ourselves and the rest of the world how great we are. But it seems we’d rather watch “Honey Boo Boo” than make a small sacrifice in the name of great discovery.

The author of the epistle of James wrote that “Faith without works is dead.” The same can be said of greatness. Greatness without works is dead. We Americans do a good job of wrapping ourselves in the flag and telling ourselves and anyone else within earshot how great we are, yet we seemed little inclined to demonstrate that greatness by unflinchingly and unselfishly doing what needs to be done to make the world a better, more understandable place today. Altruism has become a sin rather than a virtue to generations deluded by Ayn Rand and other intellectual midgets of the Me Generation. Courage to plunge into the unknown has been replaced by fear of the unknown. In our endeavor to secure comfort for ourselves at the expense of our posterity, we have begun to venerate bookkeepers and vilify adventurers. None of this bodes well for our claim of being the greatest nation on Earth.

If we Americans are going to avoid devolution into the greatest blowhards on Earth, we need to replace hollow words with solid deeds. Feeding our minds and souls with creepy voyeurism and shallow criticism is no longer an option, for—despite the temporary satisfaction of feeling superior to those we watch and judge—we, as we doze off before the television, are left feeling more hollow and dissatisfied than before.

Greatness without works is dead. A nation that claims to be great, yet that does nothing to achieve and maintain that greatness, will wither and die. We are now a nation in decline, but we can reverse it and become what we once were—a people that inspired ourselves and others.

To reverse our decline, we need to rediscover, and re-embrace, the words spoken by Kennedy as he began his presidency, “…ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” To that, I would add ask what you can do, what we can do, for our world.

What can we do for our world? We can elect political leaders who challenge us to be better, rather than ones who encourage us to be dissatisfied. We can learn and accept the limits of our opinions—especially when those opinions are crushed by the cold, hard, and often brutal weight of evidence. We can contribute blood, toil, tears, sweat—and money—to solving the great problems that face civilization today and continuing the unflinching exploration of our inner and outer universes.

That is what Wegener’s generation did. That is what Ewing’s, Vine’s, Worzel’s, Heezen’s, and Tharp’s generation did. That is what our generation did before we lost our way.

We’ve done it before. We—ourselves and our successors—can do it again.

New Frontiers

Posted by AbyssWriter on 10/30/12 • Categorized as Commentary,Exploration

[EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the text of a speech I gave at the 30th Friends of the Library Book & Author Dinner at the Indian Creek Yacht and Country Club in Kilmarnock, Va., on October 29, 2012.]

Alfred Wegener in Greenland

The theory of continental drift is 100 years old this month.

Alfred Wegener, the father of continental drift and one of the main characters of my first book, Upheaval from the Abyss, was a consummate explorer—both in the physical and intellectual realms. By October 1912, when Wegener described his theory of how the major features of the Earth’s surface rearrange themselves over geologic time, he had established himself as a pioneer explorer of the atmosphere as well as the poles. He used kites to measure characteristics of the atmosphere. He and his brother, Kurt, set an endurance record for flight in a balloon. He had been on one expedition to Greenland, and was set to go on the second of ultimately four expeditions to the ice-bound island.

His restlessness extended into his scholarly research. The main incident that triggered the events I chronicle in my book occurred in 1910, when he looked at a map and realized the similarity in shapes of the Atlantic coasts of South America and Africa were likely more than coincidence—that they had once been joined and drifted apart. In 1911, he published a major book on the thermodynamics of the atmosphere. In 1921 he published a monograph on the origin of moon craters in which he argued, on the basis of experiments he conducted, that they were created by asteroid impacts. In 1924, he and his father-in-law, Wladimir Koeppen, published a major book on earth’s past climates. And from 1915 to 1930, he published four editions of the work for which he is best know, The Origin of Continents and Oceans, in which he describes his theory of continental drift.

Throughout his too-short life—he died at age 50 on his last expedition to Greenland—Wegener, a German, embodied the frontier mythos that Americans today take for granted. He was constantly pushing the envelope, not letting geographic or academic boundaries bar him from following evidence wherever it led. He persisted in pursuing his ideas despite the withering fire of critics more interested in protecting their position than in open and honest inquiry. He did what he thought was right, even if it meant risking, and losing, his life on a Greenland glacier as he tried to ensure the welfare of men he, as expedition leader, was responsible for.

Many of the other characters in Upheaval from the Abyss embodied that as well. From Doc Ewing, who left a hardscrabble life on the Staked Plains of Texas for a life-long journey of discovery of the way the Earth, moon, and other planets worked; from the cores of young scientists and technicians—such as Al Vine, Joe Worzel, and Bruce Heezen—who joined Ewing on his quest; from Marie Tharp, who broke free of the limited suite of roles men of the time allowed women to fill, mapping the ocean floor and making the key observation that forced a scientific world that had resisted Wegener’s ideas to reconsider; none of them were content with a gray-flannel straitjacketed existence. They spent, and in some cases, gave their lives seeking to discover and understand what lay beyond the literal and figurative horizon.

Fifty years ago last month, President John F. Kennedy harnessed that frontier mythos when he launched the nation on another quest: to put send men to the moon and bring them back safely to Earth. His challenge included these famous words:

We lived up to Kennedy’s challenge. Most of us remember that fateful night in July 1969 when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to set foot on a world other than Earth. (I watched it with my parents on a television in a room at Perry’s Motel in Hot Springs, Ark.) That same decade we sent two men, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh, to the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench—the deepest point of the world’s oceans. In the decade or two afterward Kennedy’s speech, we sent spacecraft on a voyage beyond the boundaries of our solar system. We sent probes to Mars, Jupiter, Venus, and other planets; built a permanent outpost in space, discovered at the bottom of the ocean unique ecosystems that do not require energy from the light of the sun; decoded the genome; and nearly eradicated a number of devastating infectious diseases around the world.

But in the twenty first century the frontier mythos that drove us further seems to have fizzled. Those of us inspired by Kennedy’s words in our youth seem to have forgotten them as we age. We and our following generations have become so distracted by 24-hour non-news, unreality television, and inane online chatter that we can [scarcely] be bothered to make the sacrifices required to make the world better for us and our fellows. Where we once did what needed to be done despite cost, effort, and lives, we now fight over every last cent we can keep for ourselves and demand to know why we should do anything for anyone else.

The science that fueled the tremendous progress of the years after World War II, that made the advances I mentioned possible, and that helped change this nation from a largely agrarian backwater (with promise) into a global power, we have largely turned our backs on. It is no longer considered desirable to ask the big questions that made it possible for us to reach the surface of the moon or the bottom of the ocean. It is no longer considered worthwhile to consider the advice of scientists who spend their lives studying Earth’s life, climate, and oceans and warn us about the damage we are inflicting upon our planet—we have been told that scientists are all frauds, and we accept such assertions on faith.

Rather than embrace exploration and discovery as we had in the past, we have enthusiastically embraced what the writer and scientist Isaac Asimov once called the “cult of ignorance”:

Nevertheless—as the rhetoric of this election season as most other election seasons remind us—we love to tell ourselves and the rest of the world how great we are. But it seems we’d rather watch “Honey Boo Boo” than make a small sacrifice in the name of great discovery.

The author of the epistle of James wrote that “Faith without works is dead.” The same can be said of greatness. Greatness without works is dead. We Americans do a good job of wrapping ourselves in the flag and telling ourselves and anyone else within earshot how great we are, yet we seemed little inclined to demonstrate that greatness by unflinchingly and unselfishly doing what needs to be done to make the world a better, more understandable place today. Altruism has become a sin rather than a virtue to generations deluded by Ayn Rand and other intellectual midgets of the Me Generation. Courage to plunge into the unknown has been replaced by fear of the unknown. In our endeavor to secure comfort for ourselves at the expense of our posterity, we have begun to venerate bookkeepers and vilify adventurers. None of this bodes well for our claim of being the greatest nation on Earth.

If we Americans are going to avoid devolution into the greatest blowhards on Earth, we need to replace hollow words with solid deeds. Feeding our minds and souls with creepy voyeurism and shallow criticism is no longer an option, for—despite the temporary satisfaction of feeling superior to those we watch and judge—we, as we doze off before the television, are left feeling more hollow and dissatisfied than before.

Greatness without works is dead. A nation that claims to be great, yet that does nothing to achieve and maintain that greatness, will wither and die. We are now a nation in decline, but we can reverse it and become what we once were—a people that inspired ourselves and others.

To reverse our decline, we need to rediscover, and re-embrace, the words spoken by Kennedy as he began his presidency, “…ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” To that, I would add ask what you can do, what we can do, for our world.

What can we do for our world? We can elect political leaders who challenge us to be better, rather than ones who encourage us to be dissatisfied. We can learn and accept the limits of our opinions—especially when those opinions are crushed by the cold, hard, and often brutal weight of evidence. We can contribute blood, toil, tears, sweat—and money—to solving the great problems that face civilization today and continuing the unflinching exploration of our inner and outer universes.

That is what Wegener’s generation did. That is what Ewing’s, Vine’s, Worzel’s, Heezen’s, and Tharp’s generation did. That is what our generation did before we lost our way.

We’ve done it before. We—ourselves and our successors—can do it again.

Share this: