EDITOR’S NOTE: This was originally posted to Facebook, but I thought this essay deserved a more permanent home—DML.

MECHANICSVILLE, Va.—Attention my fellow writers:

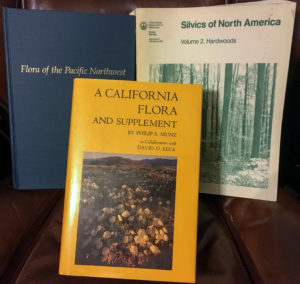

MECHANICSVILLE, Va. — These are some of the tools used when I allegedly mansplained the characteristics of some species of trees to a fellow writer.

I probably should have brought this up for Festivus, but I didn’t. Yet I feel the need to get something off my chest before the year is out.

When you ask someone to critique your work, be willing to consider—just consider, not necessarily comply with — the critique.

Some months ago, a woman writer whose prose I have found to be sublimely beautiful asked for volunteers to critique a new story she was in the process of writing.

I eagerly said yes, hoping to get a glimpse of divine prose before its revelation to the public. She included me among a group of people in a Facebook chat allowed to peek at the draft.

I was not disappointed. Her prose was as phenomenal as I could have wished. It brought me to tears (of sympathy with her main character, who was suffering great pain). At some point over the course of the evening, I told her that her prose was beautiful.

Yet, I had some questions. I am a professional editor, of course.

Keeping in mind that other people were part of the thread, and not wanted to blow up their bandwidth unnecessarily, I was terse in my questions. That aspect of what happened I must own, but it also reflects my preference when my own work is getting critiqued in a workshop: Spare the throat-clearing, get to the point.

As I remember, I had three questions: 1) a sentence that didn’t make sense as written; 2) a word that did not exist as far as I could find; and 3) an action involving a tree that did not make sense given the character’s circumstances and what I knew of that particular group of trees.

As the night wore on, I got the impression that the writer might be irritated, so I preemptively apologized given that my just-the-questions approach might have rubbed her the wrong way. I also, at least once that evening if not more often, told her how beautifully written the story was—I was and am being sincere in saying that. It was.

So what happened?

First—some hours after my preemptive apology—she sent a private message that implied I lacked maturity and that assumed (because of my appearance) that I was emboldened by white privilege.

I fumed, but I let that go.

Then—more hours later—she wrote to me, via the critique group, a long treatise on how I was “mansplainin’ ” with my questions about the story.

That was more than I could let go.

You can question my maturity all you want to, but if you skate too far in one direction you’re likely to find yourself on thin ice. I’ve been through my share of trauma, too, and I’m somehow still here. It may not be sufficient to earn me the title “mature,” but I have a decent payload of hard-earned experience that some might mistake for maturity.

Don’t assume that, because I pass the paper-bag test, that I’m white. I grew up with a hell of a lot of white people who would have gleefully tried to kill me had they known my racial background. I know what I was under Louisiana law until 1983, and it wasn’t “white.”

Now let’s get to the “mansplainin’.” Again, I am a professional editor. I would be remiss in my responsibility if I didn’t question prose that, well, raised questions.

So—unless you’ve told me you’re writing fantasy (she didn’t)—if you have an inanimate object engaging in an action, expect a question if it’s something an inanimate object can’t normally do. For example, a baseball can roll off a table; It cannot “observe” the pitcher, catcher or batter as it travels to the plate.

In the writer’s case, it involved a statue (I think). It didn’t make sense to me, so I asked about it. She said it was an allusion to Rilke and she sent me a link to the poem.

All she needed to do was say it was an allusion to Rilke. That would have—and did—satisfy me.

The link to the poem was gravy. I enjoyed it. I love Rilke, but I have not read everything he has written and I should not be treated as an idiot for: a) not having done so; and b) not remembering everything of his that I have read.

As for the word, I could not find it online. I did not find it in my Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (the abridged one) or in my Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (the unabridged one that strains my back every time I pull it off the bookshelf).

So what should a responsible editor do? Question the word choice, of course.

The writer did not respond to that question. All she would have needed to say is that: a) she’s seen it used elsewhere; or b) she just liked the way it sounded.

Personally, I would have been happy with either answer, but especially with (b). I liked the way it sounded, too. That doesn’t make it a word, but it was her story—a work of fiction—and it is OK for her to create it.

But it is also reasonable, actually responsible, for an editor to ask about it.

Now we get to the “mansplainin’ ” bit. In the story, the main character is a woman tortured by a lost love that she could not emotionally escape. The hold of that lover was strong, unyielding and undying.

In one scene, the character is along a creek in the Pacific Northwest. A grizzly walks by, and she steps close to it hoping that it will attack and end her misery. Instead, the bear passes by, and she then turns and embraces—puts her arms around—a tree. The writer identified the tree as an alder.

The action struck me as her returning to embrace this overpowering, long-lasting love for whomever it was she had lost. I can be misinterpreting the action, but I can see no other reason for it being in a fairly short short story where that former love is burning through her like an underground coal mine fire that no amount of water can extinguish.

My question in this instance was about the choice of tree. Alders (genus Alnus) are a group of mostly quick-growing but relatively small and short-lived trees that are frequently found in wetland areas such as stream-sides.

How do I know this? Not because I have a pair of balls and sometimes inconveniently swinging penis that gets tangled in my boxers. I know this because I have traveled over a good chuck of North American forests where I have encountered several species of alders in the wild. Not only that, but I am a forest geographer who has spent a lot of time doing fieldwork in those North American forests.

I helped my grandparents in Maine cut up alder growing on their land and put it in their wood stove to warm their house.

I have collected alder specimens from a hell of a lot of states in the U.S.

I have a nice collection of North American floras to consult, such as Hitchcock and Cronquist’s Flora of the Pacific Northwest (where the story was set), Munz’s A California Flora and Supplement (also geographically relevant), and both volumes of the USDA Forest Service publication Silvics of the United States, of which Volume 2 includes entries on hardwood species including alders.

From Manitoba and Saskatchewan south to the Mexican border, from the Rockies east to the Atlantic coast, I have seen my share of alders: thousands if not tens of thousands of alders in the wild over the past three decades. And you know what?

If you put your arms around most of the ones I’ve seen, you’d still be able to whack yourself in the back of the head with both hands while you do it.

The fact is that most alders from the Rockies east are little more than glorified shrubs. For those that get to any size (for alders, anyway), you can put a hand around the trunk, not one or both arms.

There is one western species, red alder (Alnus rubra) that can get to three feet in diameter, but that species still has a problem with respect to the story: Individuals rarely live longer than 100 years (according to Silvics of the United States). That’s a damned short time compared to other riparian species that can live several centuries if not more than a millennium.

So the alder invoked in the story did not ring true for the action taken by the character. When your character cannot escape the clutches of a searing, enduring love, it seems better to have that character embrace a tree species that more adequately symbolizes strength and endurance.

The writer had plenty of other options. Other species also found along streams in the Pacific Northwest get bigger and live longer—thus are better alternatives for the action taken by the character in the story.

The writer preferred to attack me rather than consider them.

My guess is that a lot of people who read the story—and who have encountered alders in places other than the narrow strip along the Pacific Coast where red alder is found—will likewise go “Huh?” when they read the passage where the character embraces the tree. It will sound as an unnecessarily false note in an otherwise exquisite performance.

So, fellow writers, when you find yourself on the receiving end of a critique, why vehemently defend one choice when other available options will work better? When you find that impulse rise, examine it before lashing out at a person who is only trying to help make an excellent story perfect.

And don’t accuse a male critic of “mansplainin’ ” when they argue not from their gender but from decades of fieldwork and study—and even consultation of relevant sources at their disposal (within 15 feet of their desk) before they raised the questions in the first place?

When someone critiques your work, more often than not, they are just critiquing your work—not you. There is a difference.

–30–

The Art of Receiving (or Not) a Critique

Posted by AbyssWriter on 12/31/16 • Categorized as Commentary,Literary Criticism

EDITOR’S NOTE: This was originally posted to Facebook, but I thought this essay deserved a more permanent home—DML.

MECHANICSVILLE, Va.—Attention my fellow writers:

MECHANICSVILLE, Va. — These are some of the tools used when I allegedly mansplained the characteristics of some species of trees to a fellow writer.

I probably should have brought this up for Festivus, but I didn’t. Yet I feel the need to get something off my chest before the year is out.

When you ask someone to critique your work, be willing to consider—just consider, not necessarily comply with — the critique.

Some months ago, a woman writer whose prose I have found to be sublimely beautiful asked for volunteers to critique a new story she was in the process of writing.

I eagerly said yes, hoping to get a glimpse of divine prose before its revelation to the public. She included me among a group of people in a Facebook chat allowed to peek at the draft.

I was not disappointed. Her prose was as phenomenal as I could have wished. It brought me to tears (of sympathy with her main character, who was suffering great pain). At some point over the course of the evening, I told her that her prose was beautiful.

Yet, I had some questions. I am a professional editor, of course.

Keeping in mind that other people were part of the thread, and not wanted to blow up their bandwidth unnecessarily, I was terse in my questions. That aspect of what happened I must own, but it also reflects my preference when my own work is getting critiqued in a workshop: Spare the throat-clearing, get to the point.

As I remember, I had three questions: 1) a sentence that didn’t make sense as written; 2) a word that did not exist as far as I could find; and 3) an action involving a tree that did not make sense given the character’s circumstances and what I knew of that particular group of trees.

As the night wore on, I got the impression that the writer might be irritated, so I preemptively apologized given that my just-the-questions approach might have rubbed her the wrong way. I also, at least once that evening if not more often, told her how beautifully written the story was—I was and am being sincere in saying that. It was.

So what happened?

First—some hours after my preemptive apology—she sent a private message that implied I lacked maturity and that assumed (because of my appearance) that I was emboldened by white privilege.

I fumed, but I let that go.

Then—more hours later—she wrote to me, via the critique group, a long treatise on how I was “mansplainin’ ” with my questions about the story.

That was more than I could let go.

You can question my maturity all you want to, but if you skate too far in one direction you’re likely to find yourself on thin ice. I’ve been through my share of trauma, too, and I’m somehow still here. It may not be sufficient to earn me the title “mature,” but I have a decent payload of hard-earned experience that some might mistake for maturity.

Don’t assume that, because I pass the paper-bag test, that I’m white. I grew up with a hell of a lot of white people who would have gleefully tried to kill me had they known my racial background. I know what I was under Louisiana law until 1983, and it wasn’t “white.”

Now let’s get to the “mansplainin’.” Again, I am a professional editor. I would be remiss in my responsibility if I didn’t question prose that, well, raised questions.

So—unless you’ve told me you’re writing fantasy (she didn’t)—if you have an inanimate object engaging in an action, expect a question if it’s something an inanimate object can’t normally do. For example, a baseball can roll off a table; It cannot “observe” the pitcher, catcher or batter as it travels to the plate.

In the writer’s case, it involved a statue (I think). It didn’t make sense to me, so I asked about it. She said it was an allusion to Rilke and she sent me a link to the poem.

All she needed to do was say it was an allusion to Rilke. That would have—and did—satisfy me.

The link to the poem was gravy. I enjoyed it. I love Rilke, but I have not read everything he has written and I should not be treated as an idiot for: a) not having done so; and b) not remembering everything of his that I have read.

As for the word, I could not find it online. I did not find it in my Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (the abridged one) or in my Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (the unabridged one that strains my back every time I pull it off the bookshelf).

So what should a responsible editor do? Question the word choice, of course.

The writer did not respond to that question. All she would have needed to say is that: a) she’s seen it used elsewhere; or b) she just liked the way it sounded.

Personally, I would have been happy with either answer, but especially with (b). I liked the way it sounded, too. That doesn’t make it a word, but it was her story—a work of fiction—and it is OK for her to create it.

But it is also reasonable, actually responsible, for an editor to ask about it.

Now we get to the “mansplainin’ ” bit. In the story, the main character is a woman tortured by a lost love that she could not emotionally escape. The hold of that lover was strong, unyielding and undying.

In one scene, the character is along a creek in the Pacific Northwest. A grizzly walks by, and she steps close to it hoping that it will attack and end her misery. Instead, the bear passes by, and she then turns and embraces—puts her arms around—a tree. The writer identified the tree as an alder.

The action struck me as her returning to embrace this overpowering, long-lasting love for whomever it was she had lost. I can be misinterpreting the action, but I can see no other reason for it being in a fairly short short story where that former love is burning through her like an underground coal mine fire that no amount of water can extinguish.

My question in this instance was about the choice of tree. Alders (genus Alnus) are a group of mostly quick-growing but relatively small and short-lived trees that are frequently found in wetland areas such as stream-sides.

How do I know this? Not because I have a pair of balls and sometimes inconveniently swinging penis that gets tangled in my boxers. I know this because I have traveled over a good chuck of North American forests where I have encountered several species of alders in the wild. Not only that, but I am a forest geographer who has spent a lot of time doing fieldwork in those North American forests.

I helped my grandparents in Maine cut up alder growing on their land and put it in their wood stove to warm their house.

I have collected alder specimens from a hell of a lot of states in the U.S.

I have a nice collection of North American floras to consult, such as Hitchcock and Cronquist’s Flora of the Pacific Northwest (where the story was set), Munz’s A California Flora and Supplement (also geographically relevant), and both volumes of the USDA Forest Service publication Silvics of the United States, of which Volume 2 includes entries on hardwood species including alders.

From Manitoba and Saskatchewan south to the Mexican border, from the Rockies east to the Atlantic coast, I have seen my share of alders: thousands if not tens of thousands of alders in the wild over the past three decades. And you know what?

If you put your arms around most of the ones I’ve seen, you’d still be able to whack yourself in the back of the head with both hands while you do it.

The fact is that most alders from the Rockies east are little more than glorified shrubs. For those that get to any size (for alders, anyway), you can put a hand around the trunk, not one or both arms.

There is one western species, red alder (Alnus rubra) that can get to three feet in diameter, but that species still has a problem with respect to the story: Individuals rarely live longer than 100 years (according to Silvics of the United States). That’s a damned short time compared to other riparian species that can live several centuries if not more than a millennium.

So the alder invoked in the story did not ring true for the action taken by the character. When your character cannot escape the clutches of a searing, enduring love, it seems better to have that character embrace a tree species that more adequately symbolizes strength and endurance.

The writer had plenty of other options. Other species also found along streams in the Pacific Northwest get bigger and live longer—thus are better alternatives for the action taken by the character in the story.

The writer preferred to attack me rather than consider them.

My guess is that a lot of people who read the story—and who have encountered alders in places other than the narrow strip along the Pacific Coast where red alder is found—will likewise go “Huh?” when they read the passage where the character embraces the tree. It will sound as an unnecessarily false note in an otherwise exquisite performance.

So, fellow writers, when you find yourself on the receiving end of a critique, why vehemently defend one choice when other available options will work better? When you find that impulse rise, examine it before lashing out at a person who is only trying to help make an excellent story perfect.

And don’t accuse a male critic of “mansplainin’ ” when they argue not from their gender but from decades of fieldwork and study—and even consultation of relevant sources at their disposal (within 15 feet of their desk) before they raised the questions in the first place?

When someone critiques your work, more often than not, they are just critiquing your work—not you. There is a difference.

–30–

Share this: